Grounded

What happened: We sail past Cowan Cowan on Moreton Island as the sun rises above the dunes. The steady wind from the south west is somewhere between 15 and 20 knots though as we turn into the main channel we bring it forward of the beam and so it becomes 20 and then 22 knots. We trim the sails. Wish has the helm. He is wearing his spare glasses because he has, half an hour before, knocked his glasses off as he manhandled the throwing lifebuoy into a bracket on the aft quarter. The glasses, of course, flew into the water and are lost to the bay.

I have been thinking, as I was on watch for the first few hours of our journey, about this voyage north, reminiscing about our previous winter migrations. I am looking forward to seeing whales. I am imagining us anchored off one of the islands we’ve anchored off before on our annual trips north. So many sunrises and sunsets on the water. Some heart stopping moments of beauty.

I think, now that Wish has the helm, that soon I’ll make breakfast.

A ship is coming up the channel behind us. In the far distance it looks as though a ship is coming towards us the other way. “I’ll go just outside the channel to give them room,” says Wish.

The first nudge of earth below the keel is a shock. Wish immediately swings the wheel to try to round us off and back into deep water but that turns us into the wind and stalls us. I dive for the switch and turn on the motor. Wish starts to try to drive us out but we are stuck fast. Worse, the wind and the outgoing tide are pushing us further into the sand. Wish keeps trying to manoeuvre. The swells are smacking us and jarring us into the banks. The pounding starts to throw things around below decks. I go below. We always pack everything away before we go but the pounding and jarring is shaking the catches on the cupboards and things are beginning to fly out. I rapidly relatch and race back to the cockpit.

There is a terrible crack. We know something bad has happened to the keel or the rudder. If it is the keel and it goes, the boat will tip over from the weight of the mast with no counterbalance. Inkwindi is cold-moulded, double-diagonal King Billy Pine, strong and supple, but the buffeting by water is severe.

Wish decides we’ll try to heel the boat further over to try to lift the keel above the sand. I take the helm and hold it hard over to starboard. Wish climbs over the safety rails and hangs off the edge of the boom outside the boat, using his weight to extreme-heel her. It gives us a small movement forward. We keep trying. Then we try the same thing on the opposite tack. Less successful. Back to hanging the boom out to starboard. We do this for minute after juddering minute, inching forward.

Wish says he thinks we should get the dinghy in the water and use the added power of its motor to help us get off but I am not happy with this. We don’t know that the puny extra 6.5 horsepower will be enough and we will have one of us in the dinghy and one on the boat with the exponential possibility of what could go wrong. “I think we need to call for help,” I say. In 40 years of sailing Wish has never had to call for outside help to get out of trouble before but he agrees, the awful below-hull crack echoing for him too.

I pick up the radio. “Pan Pan, Pan Pan, Pan Pan, this is the yacht Inkwindi, Inkwindi, Inkwindi. Our position is…. While I’m talking, I’m throwing wallets into a waterproof bag and putting it on top of our grab bag. In the event that Inkwindi starts to break up, we’ll be ready. Then I go back up on deck and we keep trying to heel Inkwindi to lessen the damage.

We’ve been asked to set off our Epirb. We do and wedge it in the cockpit. Usually one would put it in the water and tie it to the boat but for two reasons we keep it in the cockpit – first, our friend Nigel, who was in the devastating 1998 Sydney Hobart Race storm, told us that when they tied the Epirb to the boat, the string that held it to the boat snapped and it floated away; and second, we think it more useful to take it with the grabbag if we have to leave the boat.

The Dornier search plane flies over us first, dramatic and loud. Soon the Bribie Island Volunteer Marine Rescue boat arrives and throws us a tow line. The Redcliffe Coast Guard boat comes up and monitors the situation.

The tow rope is attached at the bow and they pull us free. In the deep water of the channel we drop anchor and prepare to check the boat. Wish gets his snorkel. He goes overboard and dives beneath. He can see that there is a crack in the keel all the way around but he believes it will hold. The bottom of the rudder is broken clean off but there is enough left for us to steer. Under the cabin sole there is enough water, coming in from who knows where, to have set off the automatic bilge pump. It begins to clear the water. We are not taking in more than the pump can cope with.

We decide we will be able to get back to Manly. We tell our rescuers and the water police, to whom we speak on the radio. We start off with ten minute scheduled calls to make sure we’re underway and not sinking. As we proceed, we’re confident enough of her seaworthiness that we extend that to half an hour for the nearly four-hour return to Manly. Back in the marina we tie up and survey the damage. We will have to get her out of the water to check her undersides but for the moment we have to pump out every couple of hours as about two buckets of water an hour seep in.

We start phoning hardstands but everyone is full with raceboats getting ready to race north. We get a booking for the following Monday – it’s a week away but that is the earliest we can do. Water police interview us, we make insurance calls. We pump out the bilge at two-hour intervals. By the next day we are exhausted. The adrenalin that must have flooded our bodies as we tried to save the boat and the overuse of muscle power in the process have left us aching. “I think my arms can reach my knees after hanging off the boom,” Wish says.

What worked: Extreme heeling helped us inch forward but wasn’t enough to get us off the bank on a falling tide.

What didn’t work: 1. Trying to power out. We were pushed too far onto the shoal. 2. We couldn’t just relax and wait for high tide because the water was choppy enough to be smacking the boat constantly back onto the shoal. 3. Having the chart plotter on small scale – the shoal shows up on expansion.

What we also thought of trying: 1. If we hadn’t already heard ominous cracking and called for help, Wish would have taken the spinnaker halyard on the stern of airboat and motored away just forward of a right angle to heel the boat further. 2. We would have tried taking the anchor in the dinghy and dropping it into the channel and then kedging ourselves forward.

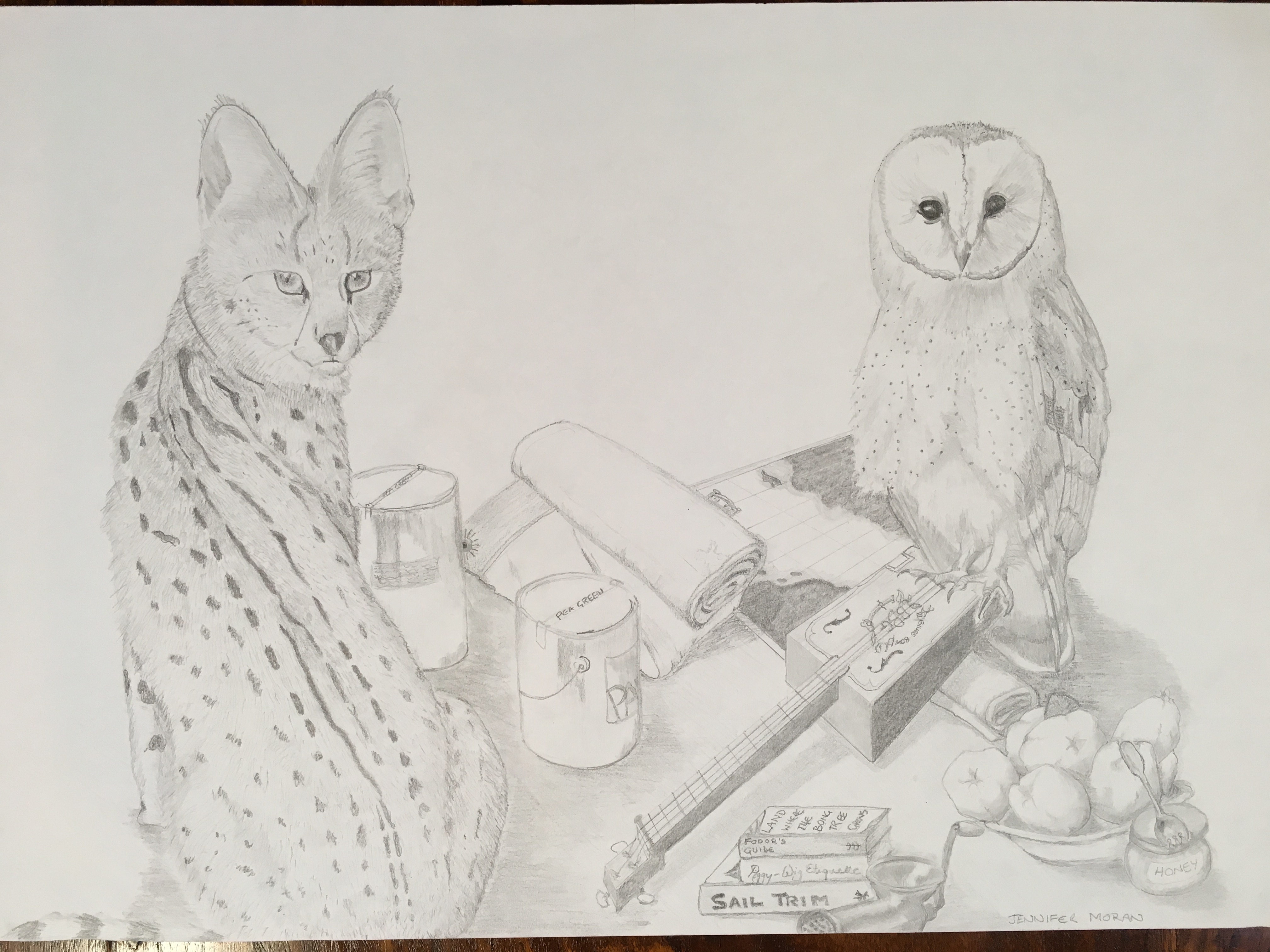

… there is nothing - absolutely nothing - half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.

- Ratty to Mole in The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame