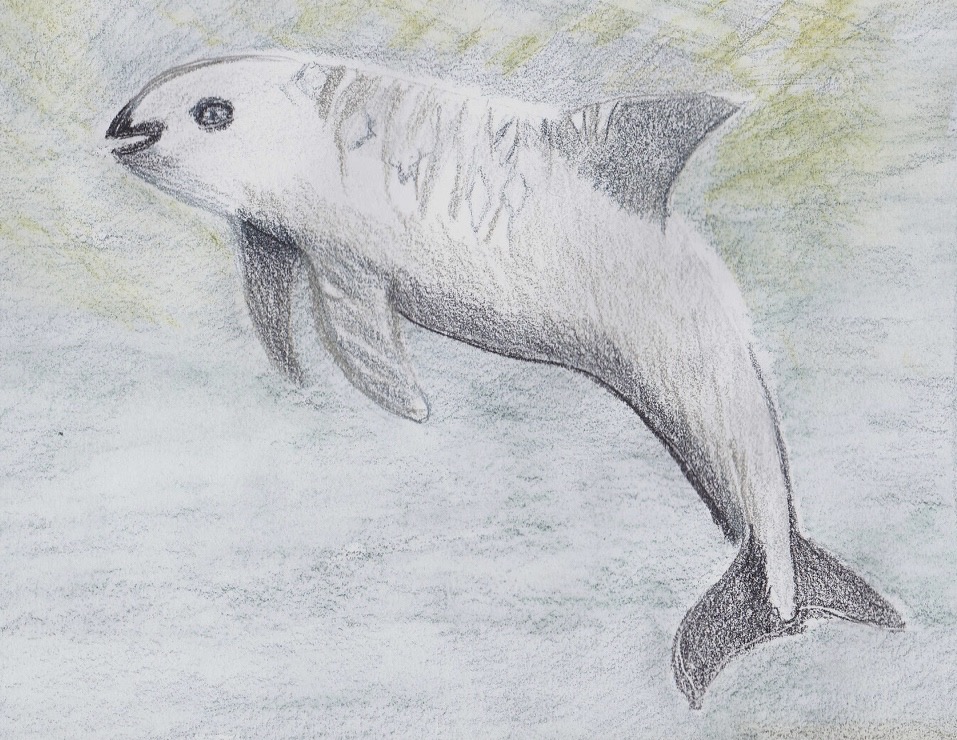

Smallest cetacean

critically endangered

This story starts in China. It starts in a restaurant kitchen, where the chef is making a soup that is said to help with fertility. The magic ingredient is the swim bladder of a totoaba. That it has no effect does little to diminish demand. The price for a single swim bladder is fantastic, reportedly more than $10,000.00 for the most impressive examples. It is this price that drives fisherman in the Mexican sector of the Gulf of California to seek out this endangered fish. In doing so, they have almost destroyed two species.

The vaquita is both the world’s smallest cetacean and its most critically endangered. There are fewer than a hundred remaining, mostly living individually rather than in pods. Found solely in the Gulf of California, their 140cm adult size lets them inhabit shallower waters, sometimes even tidal lagoons too shallow to immerse themselves completely. Unfortunately, they also venture far enough to meet with gillnets.

While protected areas deemed off limits to fishing have helped, the high price of the totoaba’s swim bladder compared to the average US$13,085.00 annual income of Mexico, means that there are always those willing to fish the reserves, and in doing so, kill vaquitas.

When you factor in the difficulty of telling a cetacean where to swim, these reserves can only do so much.

Conservation efforts try to address the economic motivation for these fishermen, buying back permits and paying a stipend to work on preservation, rather than putting out their nets. Another scheme tried to introduce a different type of fishing trawl that would not catch the vaquita. This met with less success than hoped, as the design also caught fewer fish. Proponents claim this is simply that the fisherman do not know how to utilise the different design.

In April 2015, Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto announced additional efforts to curtail the killing of vaquitas. Since then, the protected waters it inhabits have been patrolled by naval craft, making a number of arrests of illegal fishermen. It remains to be seen if their efforts will be enough.

Non government conservation organisations such as Sea Shepherd are also attempting to protect the vaquita. Working with the Mexican National Commission of Natural Protected Areas, Sea Shepherd assists with the surveillance and monitoring of the maritime reserves, as well as performing research. Oona Layolle, captain of the Sea Shepherd vessel MV Martin Sheen, made clear their resolve, stating on the Sea Shepherd webpage, “Sea Shepherd will return to the Sea of Cortez at the beginning of the next fishing season. We will come back stronger and even more prepared to do what is necessary to avoid losing another living species as a result of irresponsible human actions”.

It’s unlikely that we’ll know the extent of their success for years to come, as with fewer than 100 vaquitas, any noticeable growth in their population will take time. It’s estimated that only 25 of the remaining vaquitas are females of breeding age, with each likely to birth a single calf every second year.

The best way to ensure that efforts to save the vaquita continue is to keep them in the public eye, so ask a friend if they’ve ever heard of the world’s smallest porpoise.

… there is nothing - absolutely nothing - half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.

- Ratty to Mole in The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame